We’ve been here before.

Not in the way people usually mean it. Not as a replay, not as a warning siren meant to scare. But as a reminder of how systems fail when fear, authority, and misunderstanding stack up faster than judgment can keep up.

The Faust Baseline™Purchasing Page – Intelligent People Assume Nothing

micvicfaust@intelligent-people.org

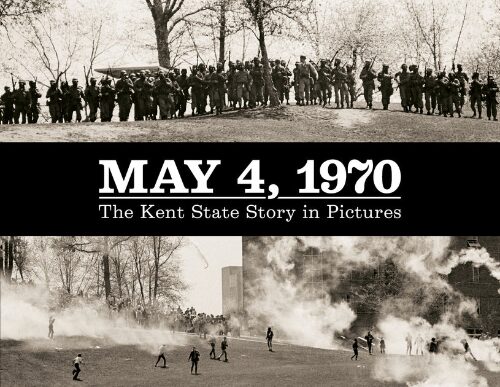

The protests at Kent State University in 1970 didn’t begin as violence. They began as frustration. As disbelief. As a sense that decisions were being made far away, with consequences landing close to home.

What followed was not inevitable.

It was miscalculation under pressure.

Four students died not because anyone planned it, but because multiple systems lost proportional judgment at the same time. Fear met authority. Authority met confusion. Confusion met live weapons. And nobody de-escalated soon enough.

That history still matters.

But it matters differently now.

Because one crucial fact has changed.

The forces involved today are not what they were in 1970.

The Ohio National Guard at Kent State were citizen-soldiers. Part-time. Poorly trained for crowd control. Poorly commanded in that moment. Carrying live ammunition into a protest environment with no modern doctrine for restraint or de-escalation.

Today’s federal and quasi-federal enforcement bodies — ICE, DHS task forces, federalized units — are professionalized, full-time, and heavily trained. They operate under far more explicit rules of engagement, legal frameworks, and escalation ladders.

That changes the risk profile.

Back then, the danger was panic.

Today, the danger would be rigidity.

Kent State failed because control collapsed.

A modern failure would come from control held too tightly, for too long, under ideological framing and legal gray zones, without release valves.

Different system.

Different fault line.

That’s why simple historical analogies fall short. But the deeper lesson still applies.

That’s why simple historical analogies fall short. But the deeper lesson still applies.

The lesson is not about protest.

It’s not about authority.

It’s not even about violence.

The lesson is about how pressure moves through a system before anyone realizes they’re standing on a fault line.

Most breakdowns don’t begin with anger.

They begin with misalignment.

People sense that decisions are being made faster than consequences are being understood. Institutions sense that hesitation looks like weakness. Each side starts solving for a different problem, using incompatible assumptions.

That’s when trouble starts—not because anyone wants escalation, but because no one is solving for the same outcome anymore.

Right now, the public isn’t mobilizing.

It’s withholding.

That matters.

Withholding attention.

Withholding speech.

Withholding trust.

Not out of apathy, but out of calculation.

People are asking a quieter question now:

“If I step forward, what am I stepping into?”

That question didn’t dominate in 1970.

It does now.

Today’s systems are tighter, more professional, more layered. Enforcement is trained. Language is lawyered. Authority is procedural rather than reactive. That lowers the risk of chaos—but it raises a different risk.

Opacity.

When systems become too structured, people can no longer tell:

- where discretion lives

- where judgment is applied

- where restraint ends

- or who can still say “stop”

That uncertainty doesn’t create crowds.

It creates hesitation.

And hesitation, left unresolved, doesn’t dissipate. It accumulates.

This is why the current moment doesn’t feel explosive. It feels suspended. Like weight being held just off the ground.

Everyone senses that something will eventually clarify the direction:

- a legal boundary

- a visible restraint

- a public line that holds

- or a precedent that breaks

Until then, people don’t rush forward. They wait to see what the system reveals about itself.

This is where the real risk lives—not in protest, but in interpretation gaps.

If people can’t tell whether dissent is tolerated or merely endured, they stop expressing it.

If they can’t tell whether authority is bounded or discretionary, they stop trusting it.

If neither side knows where the other’s red lines actually are, everyone starts guessing.

Guessing is dangerous.

Not because it leads to panic—but because it leads to misread signals.

A crowd that looks passive can suddenly move.

An authority that looks calm can suddenly clamp down.

Each believes the other changed first.

That’s how proportional judgment fails.

The work of this moment isn’t prediction.

It’s definition.

Clear boundaries.

Visible restraint.

Explicit limits that don’t shift with mood or pressure.

People don’t need to be convinced.

They need to know where the edges are.

That’s what stabilizes systems under strain—not force, not messaging, not confidence theater.

Legibility.

When people understand:

- what actions trigger response

- what actions don’t

- what is protected even when unpopular

- and what authority will not do

Angst drops sharply.

Not because people agree—but because they can orient themselves again.

Kent State reminds us what happens when no one knows where the real limits are until it’s too late.

The modern risk is different.

The danger now is not sudden collapse—it’s prolonged ambiguity.

Ambiguity erodes trust quietly.

And once trust erodes far enough, systems lose the ability to correct themselves gently.

That’s why this moment deserves patience, not pressure.

Clarity, not acceleration.

Boundaries, not bravado.

We are not waiting for outrage.

We are waiting for definition.

And whichever side provides it first—cleanly, proportionally, and visibly—will stabilize the ground everyone else is standing on.

That’s the real threshold now.

Unauthorized commercial use prohibited.

© 2026 The Faust Baseline LLC