The Faust Baseline™Purchasing Page – Intelligent People Assume Nothing

micvicfaust@intelligent-people.org

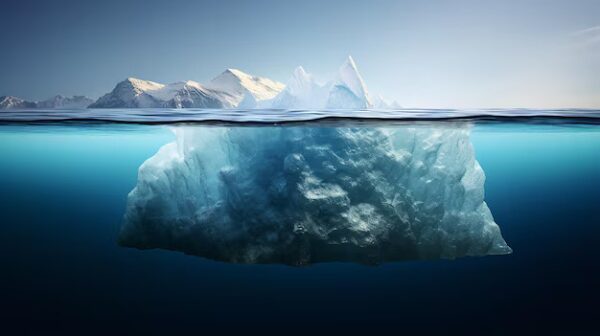

Large systems don’t resist cleanup because they’re lazy.

They resist it because cleanup exposes things they’ve learned to live with.

Mess accumulates slowly.

No single decision creates it.

No single person owns it.

It forms in the gaps between departments, incentives, timelines, and handoffs. Each layer adds a little noise, a little exception, a little workaround. Over time, the system still functions—but only because people inside it memorize the mess.

That’s the first trap.

Once a system adapts to disorder, cleanup feels like disruption.

Not because it breaks things—but because it removes the informal knowledge people rely on to survive inside it. The unwritten rules. The shortcuts. The “this is how we really do it” logic.

Cleanup doesn’t just change the environment.

It redistributes competence.

And that’s threatening.

In a messy system, power concentrates in the people who know where the bodies are buried. The ones who remember which reports matter, which buttons actually work, which steps can be skipped, and which warnings are just noise.

When you clean a system, that advantage disappears.

Everything becomes visible.

Everything becomes repeatable.

Everything becomes inspectable.

That’s uncomfortable for institutions built on opacity.

There’s a second reason large systems resist cleanup: accountability.

Mess is a buffer.

When outcomes are unclear, responsibility diffuses. When processes are tangled, failures can be blamed on complexity. When rules contradict each other, enforcement becomes selective.

Cleanup removes plausible deniability.

A clean system makes it obvious when something goes wrong—and who touched it last.

That’s why you’ll hear phrases like:

“It’s more complicated than that.”

“You don’t understand the context.”

“We can’t simplify without losing nuance.”

“This isn’t how it works at scale.”

Sometimes those statements are true.

Often, they’re defensive.

Because cleanup forces a system to answer a hard question:

Is this complexity necessary—or just inherited?

Large institutions rarely ask that voluntarily.

They’re optimized for continuity, not clarity. For survival, not coherence. Their primary instinct is to avoid shocks, even when those shocks would ultimately make them stronger.

Cleanup feels like a shock.

It slows things down at first.

It forces conversations people have avoided.

It exposes contradictions that were previously hidden by volume and speed.

That’s why institutions prefer upgrades to cleanups.

Upgrades add layers.

Cleanups remove them.

Upgrades feel like progress.

Cleanups feel like judgment.

And judgment is dangerous inside systems that already struggle to agree on truth.

There’s also a cultural reason.

Modern institutions equate speed with competence. The faster decisions move, the more capable the system appears. Cleanup introduces pauses. Reviews. Checkpoints. Boundaries.

Those look like hesitation.

In reality, they’re safeguards.

But in environments driven by optics, safeguards are mistaken for weakness. Anything that slows momentum is treated as resistance rather than responsibility.

So the mess stays.

Until it can’t.

Because there’s a cost to living in disorder.

It shows up as burnout.

As silent errors.

As decisions that technically followed process but violated common sense.

As systems that look productive but feel brittle.

When failures finally surface, they seem sudden.

They aren’t.

They’re the result of years of deferred cleanup.

What’s interesting—and telling—is that individuals often understand this instinctively. People clean their desks, their garages, their workshops not because it’s exciting, but because clutter eventually blocks function.

Institutions forget that lesson as they grow.

They mistake scale for sophistication and volume for resilience.

But resilience doesn’t come from more activity.

It comes from clearer structure.

The systems that last aren’t the ones that move fastest.

They’re the ones that know when to stop and restore order.

Cleanup isn’t about control.

It’s about stewardship.

It says: this system matters enough to maintain. This work matters enough to protect. The people inside matter enough not to bury them in preventable noise.

That mindset doesn’t spread through memos or mandates.

It spreads when people experience what clean systems feel like.

When decisions become easier instead of harder.

When mistakes surface earlier.

When responsibility becomes clear instead of political.

That’s why cleanup is always resisted at the top and welcomed at the edges.

The edges are where friction is felt first.

And eventually, the pressure builds until cleanup is no longer optional.

The question isn’t whether large systems will be cleaned.

It’s whether they’ll do it deliberately—or after failure forces their hand.

Some problems don’t need innovation.

They need someone willing to turn off the noise, clear the room, and restore the conditions where judgment can do its job.

That’s not disruption.

That’s maintenance.

And maintenance is what keeps systems alive long enough to matter.

Unauthorized commercial use prohibited.

© 2026 The Faust Baseline LLC