There was a time when tools were simple.

A hammer didn’t decide where the nail went.

A machine didn’t choose the job.

If something went wrong, you knew exactly where to look—at the person holding it.

Automation changed that.

Not all at once.

Quietly.

Piece by piece.

At first, automation helped with labor.

Then it helped with calculation.

Then with speed.

Now it helps with judgment—or claims to.

That’s where the trouble starts.

The rest of this framework is not published publicly.

It lives in the full Baseline file.

The Faust Baseline™Purchasing Page – Intelligent People Assume Nothing

Most people think the great question of automated systems is capability.

How fast can it process?

How accurate is it?

How much data can it handle?

Those questions are already answered.

The systems work.

The real question—the one almost no one wants to sit with—is this:

Who carries responsibility when the system decides?

Not who programmed it.

Not who deployed it.

Not who benefited from it.

Who is responsible at the moment the outcome lands.

Because responsibility is not a feeling.

It’s a burden that can be carried, or avoided.

In older systems, responsibility had weight.

If you made a call, you stood behind it.

If you gave an order, your name was attached.

If harm occurred, it didn’t dissolve into process.

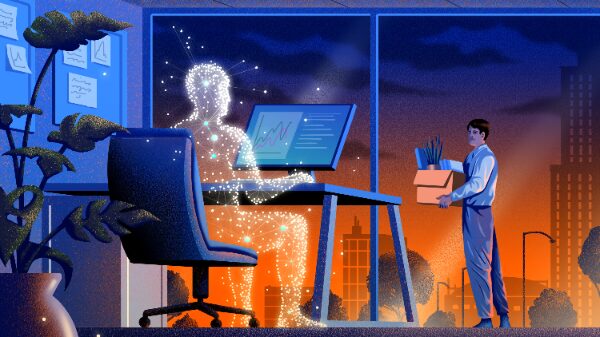

Automation offers something seductive: distance.

Distance from blame.

Distance from consequence.

Distance from having to say, “That was my call.”

And once that distance exists, people start stepping into it.

They hide behind outputs.

They point to recommendations.

They say, “The system flagged it,” or “The model suggested it,” or “That’s what the data showed.”

Notice the pattern.

Language shifts away from ownership.

But systems don’t bear responsibility.

They can’t.

They don’t suffer consequences.

They don’t feel regret.

They don’t answer for outcomes when something breaks a life, a career, or a truth.

Only humans do.

That’s why the last human responsibility in any automated system is not oversight.

It’s not tuning.

It’s not optimization.

It’s judgment under consequence.

Someone must remain willing to say:

“I see the recommendation, and I accept or reject it.”

“I understand the outcome, and I will answer for it.”

“I cannot outsource this decision, even if the system is confident.”

That moment—right there—is the last line that matters.

Once that line disappears, automation stops being a tool and becomes a shield.

A way to act without standing.

A way to decide without owning.

That’s not progress.

That’s abdication.

Good systems don’t remove human responsibility.

They concentrate it.

They make the handoff explicit.

They force a pause.

They require a human to acknowledge, “This is now on me.”

Bad systems do the opposite.

They blur authorship.

They smooth over consequence.

They reward compliance with output instead of discernment.

And over time, people forget how to carry judgment at all.

That’s the real risk.

Not that machines will think like humans.

But that humans will stop acting like humans—

responsible, accountable, and answerable.

The future doesn’t need less automation.

It needs fewer places to hide.

The last human responsibility is simple, and it cannot be delegated:

When the system speaks, a human must still decide—and be willing to stand there when the result arrives.

Everything else is convenience.

That is the line between tools and surrender.

Unauthorized commercial use prohibited.

© 2025 The Faust Baseline LLC